Reflections

When the eight participants in this project came together in

September 2021, none of us knew each other. While we all identified as being and becoming academics of working-class

heritage (WCH), we were quite a heterogeneous group. Five of us identified as

being female and three as being male. There were a range of ages stretching

from the 30s to the 50s. Geographically, we originated from an array of urban

and rural spaces across the four UK nations, and Eastern Europe. In terms of

ethnicity, everyone within this self-selecting group identified as white.

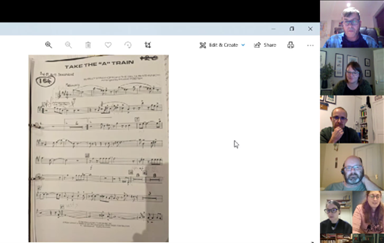

Most of our interactions and discussions were carried out

via Teams. However, on some occasions, different people within the groups met

outside of our virtual inquiry space. Some of the group came together for EuroSoTL in Manchester in May 2022, where we presented our experiences as a developing community of inquiry. Through our work, we

have highlighted that a key component for any groups such as this to work is

the need for trust, particularly when sharing intimate memories tinged with

pain, trauma and joy. Without the trust, approaches such as this one are less likely to be meaningful.

At the conceptual heart of this project was a commitment to

create narrative encounters as a means of keeping meaning open and developing

new understandings (Goodson and Gill, 2011). The narrative encounter is an unsettling one as it asks

people to be attentive to how the stories of others shape their own stories and potentially tell them something different about others as well as themselves.

The notion of unsettling is synonymous with rupture that leads to complicating

actions needed for stories to move forward, maintaining the interest of the

listener or reader. With the intention of causing disequilibrium in the hope it

would lead to moments of interrogation, there was always the concern that this

process would cause emotional dissonance. Therefore, the ethical dimensions of

the study were constantly visible, acting as a reminder to care for each other

and our stories.